I often suggest to my wife, Ragnhildur, that she should look into quantum physics.

I am not a scientist and we do have casual conversations. But it comes when we discuss her work and the decisions she must make:“...Ma chérie*, I find this to be extraordinary. I believe you should delve into quantum physics." The first time I proposed this, she pondered and naturally asked why. Since then, we've revisited the idea on multiple occasions. I'm still unsure if she fully embraces my “theories,” but I'd like to try one more time.

What is art made of? Is it a “thing” with constitutive elements? Does it have identifiable, quantifiable building blocks that we could measure and ultimately recreate? The question may sound childish or even absurd due to the intangible nature of the structures and dynamics at play in defining art. Yet, because art, like matter itself, is fundamentally based on interactions, we can't help but feel there are answers to that question. Let's take a closer look at Ragnhildur’s artworks.

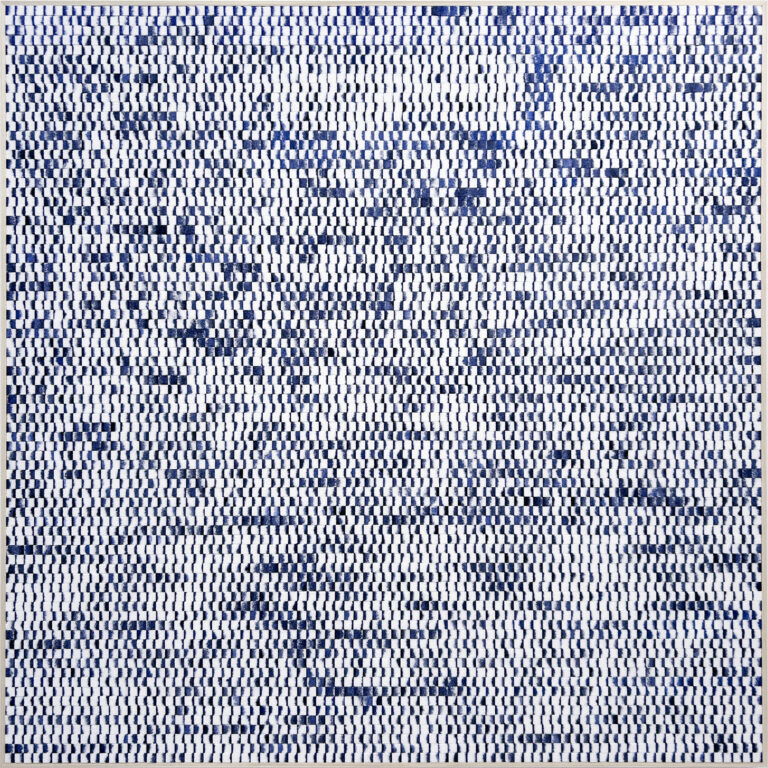

From across the room, the compositions in “Blue,” “Red,” or “Green” appear as medium-sized formats. They exhibit regular shapes, seeming flat with a two-tone grid surface. One might initially identify these as abstract paintings. Upon closer look, the assumption of encountering a traditional painting might dissolve as we realize these works are created with something other than canvas. The subject of painting may no longer be relevant. What is this?

With an even closer look, here it is: sugarcubes. Refined white sugarcubes, all similar in shape and size, partially colored. Aligned side by side, they form a larger ensemble, and the color in each cube reveals a certain logic in the arrangement. There is a pattern, a grid. A conversation with the artist reveals that a dip-dying technique was used to color the sugarcubes. A relatively simple method produces an exquisite result: Each cube is rapidly but carefully dipped in a mixture of paint and water. Sugar absorption does the job, and within seconds, color is fixed in the sugar grains. The goal is not to overfill the cubes, and there is a lot of control in the process. Yet, each cube displays a unique and distinct print of color. Despite all apparent similarities, each piece is idiosyncratic and can be seen as a multitude or the composed set of many singularities.

Quantum physics, the study of matter and energy at the most fundamental level, aims to uncover the properties and behaviors of the very building blocks of nature. One crucial aspect of quantum reality is that subatomic particles exist in different and superposed states simultaneously. Light, electrons, neutrons, or protons, for example, exist and behave as waves, like sound, and as corpuscles, like grains. From this surprising fact, any form of predictive measurement on a quantum system—such as determining the state and position of one object in a cloud of objects—can only be formulated in terms of probabilities, with a result that remains random. Unlike classical physics, where macroscopic objects have measurable and deterministic properties, quantum physics is inherently probabilistic.

A piece measuring 119 x 119 cm contains 6400 colored sugar cubes. The possible permutations with 6400 sugarcubes amount to a whopping number with 21,592 digits after 1. What if you rotate them? The number of possible outcomes, already staggering, becomes ridiculous. Add color to the mix and the different combinations, and therefore the number of possible sugarcube artworks, turns infinite. It would be normal to experience dizziness while contemplating the scale, randomness, and the vertiginous fields of the infinite. It is all very chaotic. Now, are there better options than others?

Like any other artist, Ragnhildur’s job—making art—requires making decisions. She has to come up with the best possible options to find her truth and fulfill her duty toward making art. How does she do this? How challenging can it be when you have an infinite range of possibilities to choose from? Are there better options than others? The answer is yes. There are better and more interesting options in creating art. If there weren’t, all the paintings in the world would be blank, all the music would be silent, all the books would be empty, and all the movies would be dark. By extension, the universe itself would be void and nonexistent, if not for better possibilities.

So, Ragnhildur and I often find ourselves contemplating possibilities. It goes hand in hand with the power of imagination, providing perspective. It is a chance, a privilege we must cherish and defend. Without it, life becomes meaningless, if not dangerous. Through the sugarcubes, I find art existing in the cloud of all possible options. It’s a great feeling, knowing it exists. But we need to observe it. Ragnhildur, she needs to fix it. This is why, from all the possible options, some become real. This is where and when she offers us a support to imagine or project whatever we want, and this is how, within that interaction, art may finally crystallize.

– David